|

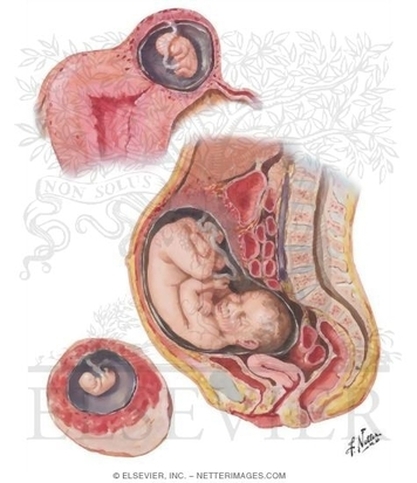

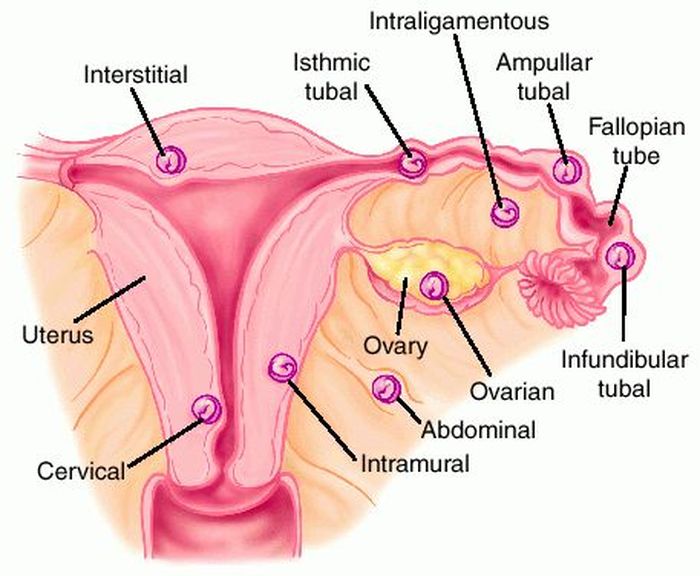

Last week’s Wednesday Wonders featured the phenomenon known as the Lithopedion or “stone baby.” This is the calcification process that a foetus that died during an abdominal pregnancy, and has remained in the abdominal cavity. But how did the foetus get there in the first place? That is the topic of this week’s Wednesday Wonders: The Abdominal Pregnancy.  Abdominal Pregnancy Abdominal Pregnancy An abdominal pregnancy occurs when a fertalized egg attaches its placenta to an organ or vascular construct outside the womb (extra-uterine). Abdominal pregnancy is an extremely serious condition as “the risk of maternal morbidity is 7-8 time greater with an abdominal ectopic pregnancy compared with other ectopic pregnancy locations and 90 times greater than an intrauterine pregnancy.[i]” There are two main types of abdominal pregnancy: Primary and Secondary abdominal pregnancy. Primary abdominal pregnancy, by far the rarest form of abdominal pregnancy, occurs either when an egg is fertilised outside of the womb and fallopian tubes, in the abdomen, or when a fertilised egg is carried from the tubes by reverse Peristalsis, depositing the fertilised ovum in the abdomen. For a pregnancy to be considered a Primary abdominal pregnancy, it must satisfy Studdiford's criteria[ii]:

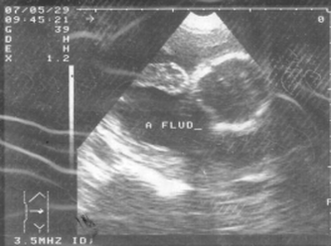

Wikipedia states that “only 24 cases had been reported by 2007” [iii] and cites Krishna Dahiya, Damyanti Sharma (2009) as the source for this information. Dahiya and Sharma do indeed state that “only 24 cases reported in the world literature,”[iv] and they in turn cite Yutaka Morita, Osamu Tutsumi et al. (1996) as the source for this information. However, I cannot see any reference in the 1996 paper to such a figure[v]. If anyone can find the original reference to the “24 cases” quotation, or can give a more up-to-date figure, please leave a comment below. Secondary abdominal pregnancy is the most common form, where an ectopic pregnancy, usually in the fallopian tubes, ruptures the tube and drifts into the abdominal cavity, where the placenta re-implants onto another organ. Sometimes, the uterus can rupture, and the foetus that has been growing in there can be released into the abdomen. So, where do the placentae of ectopic pregnancies attach? Well, attachments to the cervix, in and on the ovary, in the interstitial (the top part of the uterus) and in the caesarean scar are rare, but have been known[vi][vii], but the most common form of ectopic pregnancy is that where implantation is demonstrated in the fallopian tube. However, a pregnancy cannot continue there indefinitely, and will ether died or rupture the tube, releasing the foetus into the abdomen, where, as stated in the preceeding paragraph, the foetus can reaffix to another organ. Abdominal implantation sites include the peritoneum outside of the uterus, the rectouterine pouch (cul-de-sac of Douglas), the bowel and its mesentery, the mesosalpinx, the peritoneum of the pelvic wall and the abdominal wall, the outside of the fallopian tube and the outside of the ovary[viii]. Other rarer sites have included the liver[ix], spleen[x] (very dangerous due to the risk of uncontrollable bleeding), kidney[xi], the omentum (though rare, with only tens of cases noted)[xii][xiii], the bladder[xiv], the appendix[xv], the pancreas[xvi], and the underside of the diaphragm[xvii]. Even an aortic pregnancy[xviii] has been noted. Treatment for the condition can be interventionist, or conservative, depending on the length of gestation, whether the foetus is alive, whether it has any severe malformations (growth outside the uterus can lead to cranial asymmetry, limb deformities and severe issues relating to the nervous system), and whether there is the risk of severe internal haemorrhage to the mother with respect to the site upon which the placenta has attached. Interventionist treatment can include methotrexate if the pregnancy is caught at an early stage.[xix] This will abort the foetus, and the foetal tissue will most likely be reabsorbed by the mother’s body. If this is not possible, as the foetus is too big, or is attached to the liver or kidney, then a laparoscopy or laparotomy can be performed to remove the foetus. British surgeon Robert Lawson Tait became the first person, in April 1883, to successfully operate upon a woman with an ectopic pregnancy.[xx] Regarding the placenta, “it is recommended that the placenta be removed only if its entire blood supply can be ligated. Partial removal of the placenta is the most hazardous procedure and should not be undertaken.”[xxi] Images take from "A Rare Case Report: Primary Intrahepatic Pregnancy" The images show an ultrasound of a hepatic foetus, and MRI of the same. There have been cases where the foetus has survived to a viable stage. In the first operation of its kind in the UK, a team of 36 NHS staff removed Jayne Jones’ foetus which had been attached to her omentum. Her baby, named Billy, was placed on an incubator, and is now alive and well.[xxii] In Phoenix, USA, Nicolette Soto defied doctors’ advice to carry a Cornual Ectopic pregnancy to 32 weeks. This is strange because a Cornual Ectopic pregnancy (where the embryo implants at the end of the fallopian tube) normally ruptures between 12-14 weeks. Soto’s didn’t, and she went on to give birth to her son, Azelan Cruz Perfecto.[xxiii] In a very rare case, the only one of its kind, Meera Thangarajah carried a child to 38 weeks in her Ovary! There had been no complications, and the situation had not been picked up at a routine mid-term scan. Doctors only discovered the situation while performing a routine caesarean. The ovary was stretched to breaking point, and any little movement could have cause the sac inside to ovary to rupture. Meera’s one-in-a-million daughter is called Durga.[xxiv] In a heterotopic pregnancy, one or more foetuses implant in the uterus, while another implants in the abdomen. There are several examples where the intrauterine foetus has survived, but the abdominal foetus has not. However, there are some examples where all foetuses have survived. In Tanzania, a woman gave birth to her baby, while apparently suffering from an ovarian tumour. However, the day after she gave birth, she reported foetal movements. Doctors realised that the ovarian tumour was a misdiagnosis, and that she was carrying a child which had “attached between the anterior and posterior leaves of the right broad ligament.” She was delivered of a healthy baby boy, and both children flourished.[xxv] Finally, an English woman named Jane Ingram started off by thinking she was pregnant with one child. She had severe problems, and went to see her doctor. She was told that she was expecting twins. Still beset with severe problems, she went again, and was told she had triplets. During a scan, one of the nurses noticed something odd, and referred Jane to a specialist in London, where it was discovered that this third child was an abdominal pregnancy attached to the outside of the womb. Following one of the most complex deliveries in medical history, all three children were removed: two girls and one boy. The boy, Ronan, was the abdominal child.[xxvi] [i] An Early Abdominal Wall Ectopic Pregnancy Successfully Treated with Ultrasound Guided Intralesional Methotrexate: A Case Report. Paynesha M. Anderson, Erin K. Opfer, Jeanne M. Busch, and Everett F. Magann. Obstetrics and Gynecology International, vol. 2009, Article ID 247452, 3 pages, 2009. doi:10.1155/2009/247452

[ii] Studdiford WE. Primary peritoneal pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1942;44: pp 487–91 [iii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdominal_pregnancy [iv] Advanced Abdominal Pregnancy: A Diagnostic and Management Dilemma. Krishna Dahiya and Damyanti Sharma. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery. June 2007, 23(2): pp 69-72 [v] Successful laparoscopic management of primary abdominal pregnancy. Yutaka Morita, Osamu Tutsumi, Kazuya Kuramochi, Mikio Momoeda, Hiroyuki Yoshikawa and Yuji Taketani. Human Reproduction 1996, vol.11 DO.11 pp.2546-2547 [vi] Ectopic Pregnancies in Unusual Locations. Thomas A Molinaro, M.D., Kurt T Barnhart,M.D.,M.S.C.E. Semin Reprod Med. 2007; 25(2), pp 123-130 [vii] Ectopic pregnancies of unusual location: management dilemmas. D. V. Valsky and S. Yagel. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008; 31: pp 245–25 [viii] Abdominal Pregnancy in the United States: Frequency and Maternal Mortality. Atrash, Hani K. MD, MPH; Friede, Rew MD, MPH; Hogue, Carol J. R. PhD [ix] Diagnosis and Management of Hepatic Ectopic Pregnancy. Shippey, Stuart H. MD, LCDR, USN; Bhoola, Snehal M. MD; Royek, Anthony B. MD; Long, Mary E. MD. Obstetrics & Gynecology: February 2007 - Volume 109 - Issue 2, Part 2 - pp 544-546 [x] Splenic Pregnancy: The Role of Abdominal Imaging. Yael Yagil, MD, MHA, Nira Beck-Razi, MD, Amnon Amit, MD, Hedviga Kerner, MD, Diana Gaitini, MD. J Ultrasound Med 2007; 26: pp 1629–1632 [xi] Retroperitoneal Ectopic Pregnancy. Jung Whee Lee1, Kyung Myung Sohn and Hyun Seok Jung. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2005;184:1600-1601 [xii] Primary Omental Pregnancy. Recip Yildizhan, Mertihan Kurdoglu, Ali Kolusari, Remzi Erten. Saudi Medical Journal. 29 (4) pp 606-9 [xiii] Primary omental pregnancy. M.A. Onan, A.B. Turp, A. Saltık, N. Akyurek, C. Taskiran and O. Himmetoglu. Hum. Reprod. (March 2005) 20 (3): 807-809. [xiv] Abdominal pregnancy on the bladder wall following embryo transfer with cryopreserved-thawed embryos: a case report. R delRosario, A el-Roeiy. Fertil Steril. 1996 Nov ;66 (5): pp 839-41 [xv] Laparoscopic removal of an abdominal pregnancy adherent to the appendix after ovulation induction with human menopausal gonadotrophin. Ben-Rafael Z, Dekel A, Lerner A, Orvieto R, Halpern M, Powsner E, Voliovitch I. Hum Reprod. 1995 Jul;10(7): pp 1804-5. [xvi] Retroperitoneal subpancreatic ectopic pregnancy following in vitro fertilization in a patient with previous bilateral salpingectomy: how did it get there? Dmowski WP, Rana N, Ding J, Wu WT. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2002 Feb;19(2): pp 90-3. [xvii] Early pregnancy on the diaphragm with endometriosis. Norenberg DD, Gundersen JH, Janis JF, Gundersen AL. Obstet Gynecol. 1977 May; 49(5): pp 620-2. [xviii] Miracle baby Billy grew outside his mother's womb. Laura Collins. The Daily Mail. 31/08/2008. [xix] Management of ectopic pregnancy: a two-year study. Mahboob U, Mazhar SB. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad: JAMC 2006 18 (4): pp 34–7. [xx] Surgical Management of Ectopic Pregnancy. Author: Allahyar Jazayeri, MD, PhD, FACOG, DACOG, FSMFM [xxi] Advanced abdominal pregnancy - A review of 23 cases. R. G. White. Irish Journal of Medical Science March 1989, Volume 158, Issue 3, pp 77-78 [xxii] “Miracle baby” who grew outside the womb. The Telegraph. Wednesday 17 July 2013. [xxiii] Pregnant woman beats the odds, has miracle baby. Phoenix News. May 23, 2011 [xxiv] Ovary baby survives against odds. BBC News. 31 May 2008 [xxv] Case Report:The forgotten child—a case of heterotopic, intra-abdominal and intrauterine pregnancy carried to term. M. Ludwig, M. Kaisi, O. Bauer, and K. Diedrich. Hum. Reprod. (1999) 14 (5): pp 1372-1374. [xxvi] Ectopic triplet makes medical history. The Guardian. 10 September 1999

0 Comments

A Lithopedion is a foetus which died during an abdominal pregnancy (i.e. a pregnancy that occurred outside of the uterus) and has undergone a calcification process (calcium deposits collected upon the surface of the dead foetus and/or its membranes) which results in the foetus being surrounded by a stone-like structure. This occurs to protect the mother for the rotting corpse of her child, which could cause serious and even fatal infection. By encasing it in calcium deposits, the body is effectively defending itself against the foetal necrosis. But how could this happen in the first place? Well, there are certain conditions under which a Lithopedion can be formed:

It's not hard, then, to see why Lithopedia are a rare phenomenon! Not all Lithopedia are the same, in fact, there are three types of Lithopedion:

Let's look at some examples of Lithopedia throughout the ages. Historical evidence of Lithopedia The oldest known example of a Lithopedion was found during an archaeological excavation in the Bering Sinkhole, 41KR241, on the Edwards Plateau in Kerr County, Texas.[i] It was deemed to be a Lithokelyphos variety of Lithopedion. The site was used as a burial ground between 2000 and 7000 years ago, with the Lithopedion found in the uppers layers, suggesting a date of 3100 tears ago.[ii] The Lithopedian was described in the following way: “On the basis of the size of the posterior spinal elements, the fetus was estimated to have died at 7 to 9 months of gestation. The elements were totally skeletonised and bound by a thickened, calcified membrane.” The calcification was “amorphous” and lacking in bone tissue or structure[iii], suggesting that the stony structure had not been formed from bone tissue. A possible second early example of a Lithopedion was found during an excavation in Costebelle, France, in 1989, dating to the 4th Century. From the 1st – 5th Centuries AD, a large Roman Villa with an oil mill and press was occupied, with a nearby mausoleum[iv]. 26 Human burials were discovered, one of which, in Tomb No. 1, was the remains of a pregnant woman and her foetus were found.[v] It is this foetus which is possibly a Lithopedion, as is “shows signs of serious osseus disease”[vi]: “The well-preserved fetal skeleton, so-called “Cristobal”, discovered in the grave No. 1 of the necropolis of Costebelle presents several pathological osseous lesions: periosteal appositions on the skull vault and on the long bones; osseous resorptions of different degree, which affect first of all the extremities of the long bones (particularly in the metaphyseal region) and the external cortex of the skull vault; localised sheathed calcifications principally at about the skull vault-level and on the distal extremities of left forearm, the left hand and foot.”[vii] Olivier Dutour of the Faculty of Medicine at Marseilles believes these to be lesions from congenital syphilis, as the “general aspect of the lesions corresponds…to an infectious process.” While the alterations to the bone tissue “correspond to the criteria of the pathological changes produced by an intra-uterine infection.” However, Bruce Rothschild believes the observed phenomena to be indications of a Lithopedion: "The character of the pathology appeared to me to be calcified membranes/tissues, rather than periosteal reaction," he says. "The skull lesions are unlike those of treponemal disease (e.g., congenital syphilis) and the dramatic forearm calcification is unlike anything we have previously witnessed in over 500 cases of adult syphilis, nor in the periosteal reaction that characterizes yaws and bejel-disorders in which children (though probably not fetuses) are frequently affected."[viii][ix] Thus, the Costebelle foetus is possibly the second earliest example of a Lithopedion. The first known mention of what was thought to be a Lithopedion was by the Arab Muslim physician Albucasis (full name Abu al-Qasim Khalaf ibn al-Abbas Al-Zahrawi) who lived from 936–1013AD in Córdoba. He made many important discoveries and observations in his Magnum Opus, the thirty volume Kitab al-Tasrif, including the first description of an ectopic pregnancy, and the discovery of the hereditary nature of haemophilia. With respect to the Lithopedion, he gave the following information which regarding the removal of foetal bones from a woman’s abdomen. As far as I can see, no reference was made to calcification of said bones: “Now I myself once saw a woman who had become pregnant and the foetus had then died in utero; the again she conceived and the second foetus also died; and after a long while she got a swelling in the umbilicus which grew and eventually it opened and began to produce pus. I was called in to attend her, and I treated her for a long while but the wound did not heal up. So I applied to it certain very strongly drawing ointments, and then a bone came away from the place; then a few days passed and another bone came out; and I was mightily astonished a this, seeing that the abdomen is a place where there are no bones. I formed the opinion that these were bones from a dead foetus. So I investigated the place and got out many bones belonging to the head of the foetus. I continued this procedure and got a great number of bones, the woman being in the best of health; indeed she lived for quite a while like that, with a little pus being exuded from that place. I bring forward this uncommon occurrence here since it gives knowledge and help about the sort of treatment that the doctor who practices surgery may contrive.”[x]

"They cut through the stomach and peritoneum, and viewed the prodigious growth, which was wrinkled and formed like a turkey's crest. It was hard and brittle like a shell, and covered with what seemed like scales. The surgeons 'plunged their razors into it', but without being able to penetrate the hard shell. After wearing out the edge of their knives on the hard tumour, they fetched mauls and a drill, and finally succeeded to break it. They felt the head and right shoulder of the lithopaedion, but it was not until they had broken off a large portion of the covering shell, and seen the wonderful sight inside, that they understood what they were dealing with.”[xv] After smashing the calcified covering apart, which infuriated d’Ailleboust as it would then be “impossible to study closer the anatomy of the calcified shell and the nourishing vessels”[xvi], it was possible to see the shape and features of the foetus contained therein. Bondeson renders the scene thus: “The shape of the lithopaedion was roughly that of its rounded, calcified shell. The knees were bent, and the legs drawn up towards the chest. The feet and lower legs were fused by the calcific deposits. It could clearly be seen that the fetus was of the female sex. The head was slightly tilted to the right, and supported by the left arm. The right arm extended down towards the navel: its hand had been broken off through carelessness when the lithopaedion was extracted. The bones of the head were transparent, and the fontanelles were not closed. The skin of the head was partially covered with hair. The lithopaedion had one sole tooth, situated in the lower jaw.”[xvii] Unfortunately, after many travels, from Paris, via Venice, to Copenhagen, the Lithopedion of Madame Chatri of Sens has since disappeared. In the USA, Dr. William H. H. Parkhurst noted, in 1853, a case of a Lithopedion which had been carried for 46 years by Rebecca Eddy, neé Smith, in the town of Frankfort, Hekimer County, who died aged 77.[xviii] After becoming acquainted with Mrs Eddy in 1842, when Dr. Parkhurst originally felt the abdominal lump, the “largeness, hardness and irregularity” of which frightened him.[xix] Mrs Eddy had been married, at the age of 20, in 1795, and had become pregnant for the first time seven years later.[xx] She went through what seemed to be labour pains after an accident with a large kettle hanging over the fire: These pains diminished over the following days, eventually disappearing completely.[xxi] No investigation at the time, nor one subsequently attempted, could discern the nature of the problem, as each investigation saw a lack of pathology in the uterus.[xxii] After her death, Dr. Parkhurst performed an autopsy which revealed: “a perfect formed child…weighing 6 pounds avordepois.” It was removed “in the presence of about twenty persons…The position of the child was found with the occiput resting on the symphasis publis its face and front looking towards the spine or median line of the abdomen. It had no adhesions or connections with the mother except to the Falopian Tubes, and the blood vessels which nourished it, and which were given off from the mesenteric arteries.”[xxiii] Effectively, apart from the adhesion to the Fallopian Tube, “the child was almost floating in the abdomen.”[xxiv] The state of the foetus was described thus: “This specimen was enveloped in a firm dense cartilage. The limbs trunk and head being situated in the best possible manner, for occupying the best and least possible space; the thighs flexed upon the body and the legs upon the thighs, the elbows resting upon the knees, the arm lying close upon the side, & fore arm and hand thrown diagonally across the chest the hand resting on the side of the cranium, the face thrown down upon the chest. One lower extremity and a large share of the uper of the same side were the only parts uncovered by this cartilaginous case; and there are covered by an ossific or earthy deposit.”[xxv] The specimen should still be in Albany Medical College. Modern Examples of Lithopedia

Nearly 50 years later, when Zahra was 75, she went to hospital again with similar pains. She was referred to a specialist, Professor Taibi Ouazzani, in Rabat, who at first thought she was suffering from an ovarian tumour. What Prof. Ouazzani discovered was a large, calciferous lump. He sent her for an MRI scan, which revealed the lump to be Zahra's dead baby from nearly 50 years before. It was removed after a five hour operation, which revealed the stone baby. Below are picture of it before and after dissection. n India, a case of Twin Lithopedia was reported in a 40 year old woman who had arrived at a hospital presenting symptoms of “acute intestinal obstruction”[xxvi]. “She had abdominal distension, vomiting and absolute constipation.”[xxvii] An internal exam showed signs of a pregnancy which had somehow terminated around the fifth month of pregnancy, but nothing unusual. However, no product of the pregnancy was ever expelled from the uterus.[xxviii] Radiography showed “[t]wo radiopaque, calcified, globular shadows…on both sides of the lower abdomen”[xxix] while ultrasonography “showed two oval calcified areas on both sides of the lower abdomen.”[xxx] During the laparotomy, one Lithopedion was “morbidly adhered” to “a devitalised portion of the ileum” while the other was attached to the greater omentum.[xxxi] When the two oval masses were dissected, “two mummified and calcified foetal skeletons were recovered. Both skeletonised foetuses were of the same age (around 5 months old).”[xxxii] This is the only recorded example of Twin Lithopedia. References: [i] Three-millennium antiquity of the lithokelyphos variety of lithopedion. Bruce M. Rothschild, MD, Chistine Rothschild, RN, and Leland C. Bement, PhD. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Volume 169, Number 1. pp 140

[ii] Ibid. pp 141 [iii] Ibid [iv] The Roman Tomb No 1 of Costebelle and its Archaeological Context. Marc Borréani, Jean-Pierre Brun. L’Origine de la Syphilis en Europe: Avant ou après 1493? pp 120 [v] Paleopathological data of the osteological series from Costabelle, Hyères (3re – 6th century AD). Olivier Dutour, György Pálfi, Jacques Berato. L’Origine de la Syphilis en Europe: Avant ou après 1493? pp 125 [vi] The Roman Tomb No 1 of Costebelle and its Archaeological Context. Marc Borréani, Jean-Pierre Brun. L’Origine de la Syphilis en Europe: Avant ou après 1493? pp 120 [vii] Pathological lesion of “Cristobal”, fetus dated from the Late Roman Empire. Olivier Dutour, György Pálfi, Jacques Berato. L’Origine de la Syphilis en Europe: Avant ou après 1493? pp 133 [viii] Origins of Syphilis. Mark Rose. Archaeology. Volume 50 Number 1, January/February 1997. [ix]Dutour et al. have countered this with the following argument: “The diagnosis of Lithopedion could be pertinent if only a part of the lesions (calcifications of parietal bones and left forearm) is considered. However, as it corresponds to the infiltration of the macerated dead fetus by calcium salts, this phenomenon cannot explain by itself the “in vivo” pathological changes. Furthermore, the normal aspect of the fetal bone (without any deformation and usually mineralized), the age of the fetus estimated around 7 months and its localisation in the pelvic cavity evidenced during the excavation are not in favour of a peritoneal pregnancy (even if theoretically, a normal fetus could approach full term in 1% of extra-uterine pregnancies.” - Differential diagnosis of the lesions observed on the fetus “Cristobal”. Olivier Dutour, Michel Panuel, György Pálfi, Jacques Berato. L’Origine de la Syphilis en Europe: Avant ou après 1493? pp 139 [x] On Surgery and Instruments. Albucasis. Edited by Spink and Lewis. Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine. 1973. pp 480-2 [xi] Gynaeciorum sive de mulierum tum communibus tum gravidarum libri quotquot extant. Israel Spach. 1597. pp 479 [xii] Often, the description of the Lithopedion is erroneously attributed to Israel Spach, from a work from 1557. However, this would have been before the dissection of Madame Chatri, and is thus an impossibility. As stated, the description comes from Jean d’Ailleboust’s thesis, which was printed in Israel Spach’s Gynaeciorum sive de mulierum tum communibus tum gravidarum libri quotquot extant of 1597. [xiii] Earliest known case of a Lithopedion. Jan Bondeson MD LicSc. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Vol. 89. Jan 1996. pp 13 [xiv] ibid. pp 18 [xv] ibid. pp 13 [xvi] ibid [xvii] ib. pp 13-4 [xviii] Lithopedion from the Case of Dr. William H. H. Parkhurst, 1853. Grace Parkhurst Bernard. Bulletin of the History of Medicine. Vol. 21, 1947. pp 377-8 [xix] Ibid. pp 378 [xx] Ibid pp 380 [xxi] Ibid pp 381 [xxii] Ibid. pp 381-2 [xxiii] Ibid. pp 382 [xxiv] Ibid. [xxv] Ibid. pp 383 [xxvi] Twin Lithopaedons: a rare entity. Mishra J. M., Behera T. K., Panda B. K., Sarangi K. Singapore Medical Journal 2007; 48(9); pp 866 [xxvii] Ibid. [xxviii] Ibid. pp 867 [xxix] Ibid. [xxx] Ibid. [xxxi] Ibid. pp 866-7 [xxxii] Ibid. pp 867 |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2013

|

MOST VIEWED POSTS

© James Edward Hughes 2013

RSS Feed

RSS Feed