|

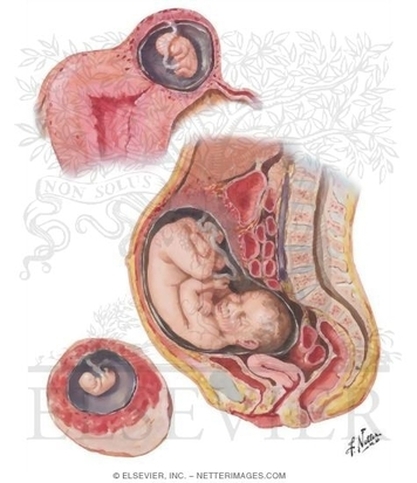

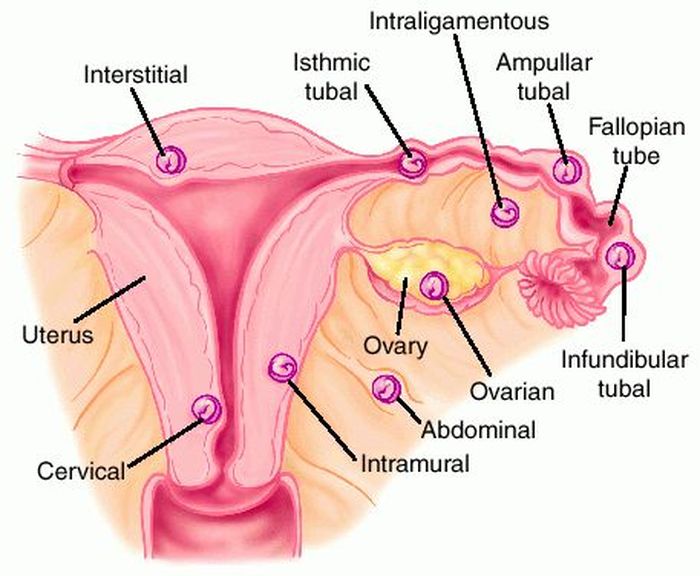

Last week’s Wednesday Wonders featured the phenomenon known as the Lithopedion or “stone baby.” This is the calcification process that a foetus that died during an abdominal pregnancy, and has remained in the abdominal cavity. But how did the foetus get there in the first place? That is the topic of this week’s Wednesday Wonders: The Abdominal Pregnancy.  Abdominal Pregnancy Abdominal Pregnancy An abdominal pregnancy occurs when a fertalized egg attaches its placenta to an organ or vascular construct outside the womb (extra-uterine). Abdominal pregnancy is an extremely serious condition as “the risk of maternal morbidity is 7-8 time greater with an abdominal ectopic pregnancy compared with other ectopic pregnancy locations and 90 times greater than an intrauterine pregnancy.[i]” There are two main types of abdominal pregnancy: Primary and Secondary abdominal pregnancy. Primary abdominal pregnancy, by far the rarest form of abdominal pregnancy, occurs either when an egg is fertilised outside of the womb and fallopian tubes, in the abdomen, or when a fertilised egg is carried from the tubes by reverse Peristalsis, depositing the fertilised ovum in the abdomen. For a pregnancy to be considered a Primary abdominal pregnancy, it must satisfy Studdiford's criteria[ii]:

Wikipedia states that “only 24 cases had been reported by 2007” [iii] and cites Krishna Dahiya, Damyanti Sharma (2009) as the source for this information. Dahiya and Sharma do indeed state that “only 24 cases reported in the world literature,”[iv] and they in turn cite Yutaka Morita, Osamu Tutsumi et al. (1996) as the source for this information. However, I cannot see any reference in the 1996 paper to such a figure[v]. If anyone can find the original reference to the “24 cases” quotation, or can give a more up-to-date figure, please leave a comment below. Secondary abdominal pregnancy is the most common form, where an ectopic pregnancy, usually in the fallopian tubes, ruptures the tube and drifts into the abdominal cavity, where the placenta re-implants onto another organ. Sometimes, the uterus can rupture, and the foetus that has been growing in there can be released into the abdomen. So, where do the placentae of ectopic pregnancies attach? Well, attachments to the cervix, in and on the ovary, in the interstitial (the top part of the uterus) and in the caesarean scar are rare, but have been known[vi][vii], but the most common form of ectopic pregnancy is that where implantation is demonstrated in the fallopian tube. However, a pregnancy cannot continue there indefinitely, and will ether died or rupture the tube, releasing the foetus into the abdomen, where, as stated in the preceeding paragraph, the foetus can reaffix to another organ. Abdominal implantation sites include the peritoneum outside of the uterus, the rectouterine pouch (cul-de-sac of Douglas), the bowel and its mesentery, the mesosalpinx, the peritoneum of the pelvic wall and the abdominal wall, the outside of the fallopian tube and the outside of the ovary[viii]. Other rarer sites have included the liver[ix], spleen[x] (very dangerous due to the risk of uncontrollable bleeding), kidney[xi], the omentum (though rare, with only tens of cases noted)[xii][xiii], the bladder[xiv], the appendix[xv], the pancreas[xvi], and the underside of the diaphragm[xvii]. Even an aortic pregnancy[xviii] has been noted. Treatment for the condition can be interventionist, or conservative, depending on the length of gestation, whether the foetus is alive, whether it has any severe malformations (growth outside the uterus can lead to cranial asymmetry, limb deformities and severe issues relating to the nervous system), and whether there is the risk of severe internal haemorrhage to the mother with respect to the site upon which the placenta has attached. Interventionist treatment can include methotrexate if the pregnancy is caught at an early stage.[xix] This will abort the foetus, and the foetal tissue will most likely be reabsorbed by the mother’s body. If this is not possible, as the foetus is too big, or is attached to the liver or kidney, then a laparoscopy or laparotomy can be performed to remove the foetus. British surgeon Robert Lawson Tait became the first person, in April 1883, to successfully operate upon a woman with an ectopic pregnancy.[xx] Regarding the placenta, “it is recommended that the placenta be removed only if its entire blood supply can be ligated. Partial removal of the placenta is the most hazardous procedure and should not be undertaken.”[xxi] Images take from "A Rare Case Report: Primary Intrahepatic Pregnancy" The images show an ultrasound of a hepatic foetus, and MRI of the same. There have been cases where the foetus has survived to a viable stage. In the first operation of its kind in the UK, a team of 36 NHS staff removed Jayne Jones’ foetus which had been attached to her omentum. Her baby, named Billy, was placed on an incubator, and is now alive and well.[xxii] In Phoenix, USA, Nicolette Soto defied doctors’ advice to carry a Cornual Ectopic pregnancy to 32 weeks. This is strange because a Cornual Ectopic pregnancy (where the embryo implants at the end of the fallopian tube) normally ruptures between 12-14 weeks. Soto’s didn’t, and she went on to give birth to her son, Azelan Cruz Perfecto.[xxiii] In a very rare case, the only one of its kind, Meera Thangarajah carried a child to 38 weeks in her Ovary! There had been no complications, and the situation had not been picked up at a routine mid-term scan. Doctors only discovered the situation while performing a routine caesarean. The ovary was stretched to breaking point, and any little movement could have cause the sac inside to ovary to rupture. Meera’s one-in-a-million daughter is called Durga.[xxiv] In a heterotopic pregnancy, one or more foetuses implant in the uterus, while another implants in the abdomen. There are several examples where the intrauterine foetus has survived, but the abdominal foetus has not. However, there are some examples where all foetuses have survived. In Tanzania, a woman gave birth to her baby, while apparently suffering from an ovarian tumour. However, the day after she gave birth, she reported foetal movements. Doctors realised that the ovarian tumour was a misdiagnosis, and that she was carrying a child which had “attached between the anterior and posterior leaves of the right broad ligament.” She was delivered of a healthy baby boy, and both children flourished.[xxv] Finally, an English woman named Jane Ingram started off by thinking she was pregnant with one child. She had severe problems, and went to see her doctor. She was told that she was expecting twins. Still beset with severe problems, she went again, and was told she had triplets. During a scan, one of the nurses noticed something odd, and referred Jane to a specialist in London, where it was discovered that this third child was an abdominal pregnancy attached to the outside of the womb. Following one of the most complex deliveries in medical history, all three children were removed: two girls and one boy. The boy, Ronan, was the abdominal child.[xxvi] [i] An Early Abdominal Wall Ectopic Pregnancy Successfully Treated with Ultrasound Guided Intralesional Methotrexate: A Case Report. Paynesha M. Anderson, Erin K. Opfer, Jeanne M. Busch, and Everett F. Magann. Obstetrics and Gynecology International, vol. 2009, Article ID 247452, 3 pages, 2009. doi:10.1155/2009/247452

[ii] Studdiford WE. Primary peritoneal pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1942;44: pp 487–91 [iii] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abdominal_pregnancy [iv] Advanced Abdominal Pregnancy: A Diagnostic and Management Dilemma. Krishna Dahiya and Damyanti Sharma. Journal of Gynecologic Surgery. June 2007, 23(2): pp 69-72 [v] Successful laparoscopic management of primary abdominal pregnancy. Yutaka Morita, Osamu Tutsumi, Kazuya Kuramochi, Mikio Momoeda, Hiroyuki Yoshikawa and Yuji Taketani. Human Reproduction 1996, vol.11 DO.11 pp.2546-2547 [vi] Ectopic Pregnancies in Unusual Locations. Thomas A Molinaro, M.D., Kurt T Barnhart,M.D.,M.S.C.E. Semin Reprod Med. 2007; 25(2), pp 123-130 [vii] Ectopic pregnancies of unusual location: management dilemmas. D. V. Valsky and S. Yagel. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2008; 31: pp 245–25 [viii] Abdominal Pregnancy in the United States: Frequency and Maternal Mortality. Atrash, Hani K. MD, MPH; Friede, Rew MD, MPH; Hogue, Carol J. R. PhD [ix] Diagnosis and Management of Hepatic Ectopic Pregnancy. Shippey, Stuart H. MD, LCDR, USN; Bhoola, Snehal M. MD; Royek, Anthony B. MD; Long, Mary E. MD. Obstetrics & Gynecology: February 2007 - Volume 109 - Issue 2, Part 2 - pp 544-546 [x] Splenic Pregnancy: The Role of Abdominal Imaging. Yael Yagil, MD, MHA, Nira Beck-Razi, MD, Amnon Amit, MD, Hedviga Kerner, MD, Diana Gaitini, MD. J Ultrasound Med 2007; 26: pp 1629–1632 [xi] Retroperitoneal Ectopic Pregnancy. Jung Whee Lee1, Kyung Myung Sohn and Hyun Seok Jung. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2005;184:1600-1601 [xii] Primary Omental Pregnancy. Recip Yildizhan, Mertihan Kurdoglu, Ali Kolusari, Remzi Erten. Saudi Medical Journal. 29 (4) pp 606-9 [xiii] Primary omental pregnancy. M.A. Onan, A.B. Turp, A. Saltık, N. Akyurek, C. Taskiran and O. Himmetoglu. Hum. Reprod. (March 2005) 20 (3): 807-809. [xiv] Abdominal pregnancy on the bladder wall following embryo transfer with cryopreserved-thawed embryos: a case report. R delRosario, A el-Roeiy. Fertil Steril. 1996 Nov ;66 (5): pp 839-41 [xv] Laparoscopic removal of an abdominal pregnancy adherent to the appendix after ovulation induction with human menopausal gonadotrophin. Ben-Rafael Z, Dekel A, Lerner A, Orvieto R, Halpern M, Powsner E, Voliovitch I. Hum Reprod. 1995 Jul;10(7): pp 1804-5. [xvi] Retroperitoneal subpancreatic ectopic pregnancy following in vitro fertilization in a patient with previous bilateral salpingectomy: how did it get there? Dmowski WP, Rana N, Ding J, Wu WT. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2002 Feb;19(2): pp 90-3. [xvii] Early pregnancy on the diaphragm with endometriosis. Norenberg DD, Gundersen JH, Janis JF, Gundersen AL. Obstet Gynecol. 1977 May; 49(5): pp 620-2. [xviii] Miracle baby Billy grew outside his mother's womb. Laura Collins. The Daily Mail. 31/08/2008. [xix] Management of ectopic pregnancy: a two-year study. Mahboob U, Mazhar SB. Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad: JAMC 2006 18 (4): pp 34–7. [xx] Surgical Management of Ectopic Pregnancy. Author: Allahyar Jazayeri, MD, PhD, FACOG, DACOG, FSMFM [xxi] Advanced abdominal pregnancy - A review of 23 cases. R. G. White. Irish Journal of Medical Science March 1989, Volume 158, Issue 3, pp 77-78 [xxii] “Miracle baby” who grew outside the womb. The Telegraph. Wednesday 17 July 2013. [xxiii] Pregnant woman beats the odds, has miracle baby. Phoenix News. May 23, 2011 [xxiv] Ovary baby survives against odds. BBC News. 31 May 2008 [xxv] Case Report:The forgotten child—a case of heterotopic, intra-abdominal and intrauterine pregnancy carried to term. M. Ludwig, M. Kaisi, O. Bauer, and K. Diedrich. Hum. Reprod. (1999) 14 (5): pp 1372-1374. [xxvi] Ectopic triplet makes medical history. The Guardian. 10 September 1999

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2013

|

MOST VIEWED POSTS

© James Edward Hughes 2013

RSS Feed

RSS Feed