|

A Lithopedion is a foetus which died during an abdominal pregnancy (i.e. a pregnancy that occurred outside of the uterus) and has undergone a calcification process (calcium deposits collected upon the surface of the dead foetus and/or its membranes) which results in the foetus being surrounded by a stone-like structure. This occurs to protect the mother for the rotting corpse of her child, which could cause serious and even fatal infection. By encasing it in calcium deposits, the body is effectively defending itself against the foetal necrosis. But how could this happen in the first place? Well, there are certain conditions under which a Lithopedion can be formed:

It's not hard, then, to see why Lithopedia are a rare phenomenon! Not all Lithopedia are the same, in fact, there are three types of Lithopedion:

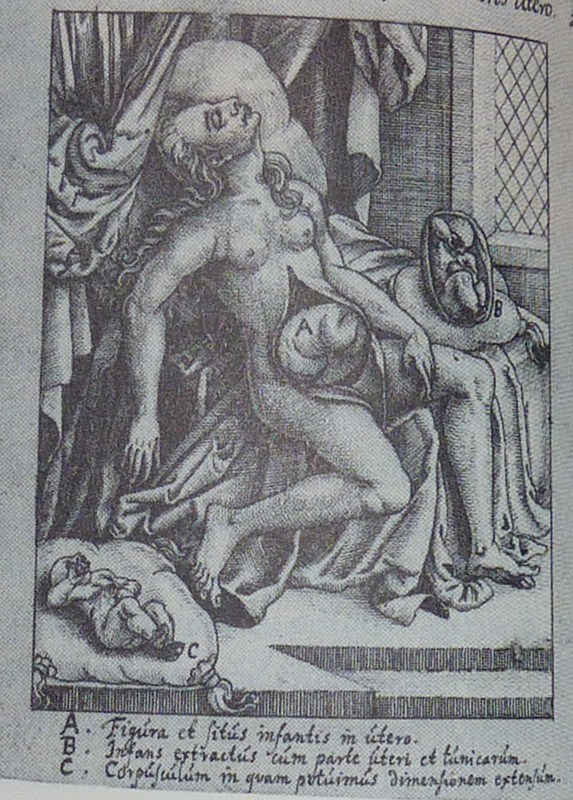

Let's look at some examples of Lithopedia throughout the ages. Historical evidence of Lithopedia The oldest known example of a Lithopedion was found during an archaeological excavation in the Bering Sinkhole, 41KR241, on the Edwards Plateau in Kerr County, Texas.[i] It was deemed to be a Lithokelyphos variety of Lithopedion. The site was used as a burial ground between 2000 and 7000 years ago, with the Lithopedion found in the uppers layers, suggesting a date of 3100 tears ago.[ii] The Lithopedian was described in the following way: “On the basis of the size of the posterior spinal elements, the fetus was estimated to have died at 7 to 9 months of gestation. The elements were totally skeletonised and bound by a thickened, calcified membrane.” The calcification was “amorphous” and lacking in bone tissue or structure[iii], suggesting that the stony structure had not been formed from bone tissue. A possible second early example of a Lithopedion was found during an excavation in Costebelle, France, in 1989, dating to the 4th Century. From the 1st – 5th Centuries AD, a large Roman Villa with an oil mill and press was occupied, with a nearby mausoleum[iv]. 26 Human burials were discovered, one of which, in Tomb No. 1, was the remains of a pregnant woman and her foetus were found.[v] It is this foetus which is possibly a Lithopedion, as is “shows signs of serious osseus disease”[vi]: “The well-preserved fetal skeleton, so-called “Cristobal”, discovered in the grave No. 1 of the necropolis of Costebelle presents several pathological osseous lesions: periosteal appositions on the skull vault and on the long bones; osseous resorptions of different degree, which affect first of all the extremities of the long bones (particularly in the metaphyseal region) and the external cortex of the skull vault; localised sheathed calcifications principally at about the skull vault-level and on the distal extremities of left forearm, the left hand and foot.”[vii] Olivier Dutour of the Faculty of Medicine at Marseilles believes these to be lesions from congenital syphilis, as the “general aspect of the lesions corresponds…to an infectious process.” While the alterations to the bone tissue “correspond to the criteria of the pathological changes produced by an intra-uterine infection.” However, Bruce Rothschild believes the observed phenomena to be indications of a Lithopedion: "The character of the pathology appeared to me to be calcified membranes/tissues, rather than periosteal reaction," he says. "The skull lesions are unlike those of treponemal disease (e.g., congenital syphilis) and the dramatic forearm calcification is unlike anything we have previously witnessed in over 500 cases of adult syphilis, nor in the periosteal reaction that characterizes yaws and bejel-disorders in which children (though probably not fetuses) are frequently affected."[viii][ix] Thus, the Costebelle foetus is possibly the second earliest example of a Lithopedion. The first known mention of what was thought to be a Lithopedion was by the Arab Muslim physician Albucasis (full name Abu al-Qasim Khalaf ibn al-Abbas Al-Zahrawi) who lived from 936–1013AD in Córdoba. He made many important discoveries and observations in his Magnum Opus, the thirty volume Kitab al-Tasrif, including the first description of an ectopic pregnancy, and the discovery of the hereditary nature of haemophilia. With respect to the Lithopedion, he gave the following information which regarding the removal of foetal bones from a woman’s abdomen. As far as I can see, no reference was made to calcification of said bones: “Now I myself once saw a woman who had become pregnant and the foetus had then died in utero; the again she conceived and the second foetus also died; and after a long while she got a swelling in the umbilicus which grew and eventually it opened and began to produce pus. I was called in to attend her, and I treated her for a long while but the wound did not heal up. So I applied to it certain very strongly drawing ointments, and then a bone came away from the place; then a few days passed and another bone came out; and I was mightily astonished a this, seeing that the abdomen is a place where there are no bones. I formed the opinion that these were bones from a dead foetus. So I investigated the place and got out many bones belonging to the head of the foetus. I continued this procedure and got a great number of bones, the woman being in the best of health; indeed she lived for quite a while like that, with a little pus being exuded from that place. I bring forward this uncommon occurrence here since it gives knowledge and help about the sort of treatment that the doctor who practices surgery may contrive.”[x]

"They cut through the stomach and peritoneum, and viewed the prodigious growth, which was wrinkled and formed like a turkey's crest. It was hard and brittle like a shell, and covered with what seemed like scales. The surgeons 'plunged their razors into it', but without being able to penetrate the hard shell. After wearing out the edge of their knives on the hard tumour, they fetched mauls and a drill, and finally succeeded to break it. They felt the head and right shoulder of the lithopaedion, but it was not until they had broken off a large portion of the covering shell, and seen the wonderful sight inside, that they understood what they were dealing with.”[xv] After smashing the calcified covering apart, which infuriated d’Ailleboust as it would then be “impossible to study closer the anatomy of the calcified shell and the nourishing vessels”[xvi], it was possible to see the shape and features of the foetus contained therein. Bondeson renders the scene thus: “The shape of the lithopaedion was roughly that of its rounded, calcified shell. The knees were bent, and the legs drawn up towards the chest. The feet and lower legs were fused by the calcific deposits. It could clearly be seen that the fetus was of the female sex. The head was slightly tilted to the right, and supported by the left arm. The right arm extended down towards the navel: its hand had been broken off through carelessness when the lithopaedion was extracted. The bones of the head were transparent, and the fontanelles were not closed. The skin of the head was partially covered with hair. The lithopaedion had one sole tooth, situated in the lower jaw.”[xvii] Unfortunately, after many travels, from Paris, via Venice, to Copenhagen, the Lithopedion of Madame Chatri of Sens has since disappeared. In the USA, Dr. William H. H. Parkhurst noted, in 1853, a case of a Lithopedion which had been carried for 46 years by Rebecca Eddy, neé Smith, in the town of Frankfort, Hekimer County, who died aged 77.[xviii] After becoming acquainted with Mrs Eddy in 1842, when Dr. Parkhurst originally felt the abdominal lump, the “largeness, hardness and irregularity” of which frightened him.[xix] Mrs Eddy had been married, at the age of 20, in 1795, and had become pregnant for the first time seven years later.[xx] She went through what seemed to be labour pains after an accident with a large kettle hanging over the fire: These pains diminished over the following days, eventually disappearing completely.[xxi] No investigation at the time, nor one subsequently attempted, could discern the nature of the problem, as each investigation saw a lack of pathology in the uterus.[xxii] After her death, Dr. Parkhurst performed an autopsy which revealed: “a perfect formed child…weighing 6 pounds avordepois.” It was removed “in the presence of about twenty persons…The position of the child was found with the occiput resting on the symphasis publis its face and front looking towards the spine or median line of the abdomen. It had no adhesions or connections with the mother except to the Falopian Tubes, and the blood vessels which nourished it, and which were given off from the mesenteric arteries.”[xxiii] Effectively, apart from the adhesion to the Fallopian Tube, “the child was almost floating in the abdomen.”[xxiv] The state of the foetus was described thus: “This specimen was enveloped in a firm dense cartilage. The limbs trunk and head being situated in the best possible manner, for occupying the best and least possible space; the thighs flexed upon the body and the legs upon the thighs, the elbows resting upon the knees, the arm lying close upon the side, & fore arm and hand thrown diagonally across the chest the hand resting on the side of the cranium, the face thrown down upon the chest. One lower extremity and a large share of the uper of the same side were the only parts uncovered by this cartilaginous case; and there are covered by an ossific or earthy deposit.”[xxv] The specimen should still be in Albany Medical College. Modern Examples of Lithopedia

Nearly 50 years later, when Zahra was 75, she went to hospital again with similar pains. She was referred to a specialist, Professor Taibi Ouazzani, in Rabat, who at first thought she was suffering from an ovarian tumour. What Prof. Ouazzani discovered was a large, calciferous lump. He sent her for an MRI scan, which revealed the lump to be Zahra's dead baby from nearly 50 years before. It was removed after a five hour operation, which revealed the stone baby. Below are picture of it before and after dissection. n India, a case of Twin Lithopedia was reported in a 40 year old woman who had arrived at a hospital presenting symptoms of “acute intestinal obstruction”[xxvi]. “She had abdominal distension, vomiting and absolute constipation.”[xxvii] An internal exam showed signs of a pregnancy which had somehow terminated around the fifth month of pregnancy, but nothing unusual. However, no product of the pregnancy was ever expelled from the uterus.[xxviii] Radiography showed “[t]wo radiopaque, calcified, globular shadows…on both sides of the lower abdomen”[xxix] while ultrasonography “showed two oval calcified areas on both sides of the lower abdomen.”[xxx] During the laparotomy, one Lithopedion was “morbidly adhered” to “a devitalised portion of the ileum” while the other was attached to the greater omentum.[xxxi] When the two oval masses were dissected, “two mummified and calcified foetal skeletons were recovered. Both skeletonised foetuses were of the same age (around 5 months old).”[xxxii] This is the only recorded example of Twin Lithopedia. References: [i] Three-millennium antiquity of the lithokelyphos variety of lithopedion. Bruce M. Rothschild, MD, Chistine Rothschild, RN, and Leland C. Bement, PhD. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Volume 169, Number 1. pp 140

[ii] Ibid. pp 141 [iii] Ibid [iv] The Roman Tomb No 1 of Costebelle and its Archaeological Context. Marc Borréani, Jean-Pierre Brun. L’Origine de la Syphilis en Europe: Avant ou après 1493? pp 120 [v] Paleopathological data of the osteological series from Costabelle, Hyères (3re – 6th century AD). Olivier Dutour, György Pálfi, Jacques Berato. L’Origine de la Syphilis en Europe: Avant ou après 1493? pp 125 [vi] The Roman Tomb No 1 of Costebelle and its Archaeological Context. Marc Borréani, Jean-Pierre Brun. L’Origine de la Syphilis en Europe: Avant ou après 1493? pp 120 [vii] Pathological lesion of “Cristobal”, fetus dated from the Late Roman Empire. Olivier Dutour, György Pálfi, Jacques Berato. L’Origine de la Syphilis en Europe: Avant ou après 1493? pp 133 [viii] Origins of Syphilis. Mark Rose. Archaeology. Volume 50 Number 1, January/February 1997. [ix]Dutour et al. have countered this with the following argument: “The diagnosis of Lithopedion could be pertinent if only a part of the lesions (calcifications of parietal bones and left forearm) is considered. However, as it corresponds to the infiltration of the macerated dead fetus by calcium salts, this phenomenon cannot explain by itself the “in vivo” pathological changes. Furthermore, the normal aspect of the fetal bone (without any deformation and usually mineralized), the age of the fetus estimated around 7 months and its localisation in the pelvic cavity evidenced during the excavation are not in favour of a peritoneal pregnancy (even if theoretically, a normal fetus could approach full term in 1% of extra-uterine pregnancies.” - Differential diagnosis of the lesions observed on the fetus “Cristobal”. Olivier Dutour, Michel Panuel, György Pálfi, Jacques Berato. L’Origine de la Syphilis en Europe: Avant ou après 1493? pp 139 [x] On Surgery and Instruments. Albucasis. Edited by Spink and Lewis. Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine. 1973. pp 480-2 [xi] Gynaeciorum sive de mulierum tum communibus tum gravidarum libri quotquot extant. Israel Spach. 1597. pp 479 [xii] Often, the description of the Lithopedion is erroneously attributed to Israel Spach, from a work from 1557. However, this would have been before the dissection of Madame Chatri, and is thus an impossibility. As stated, the description comes from Jean d’Ailleboust’s thesis, which was printed in Israel Spach’s Gynaeciorum sive de mulierum tum communibus tum gravidarum libri quotquot extant of 1597. [xiii] Earliest known case of a Lithopedion. Jan Bondeson MD LicSc. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Vol. 89. Jan 1996. pp 13 [xiv] ibid. pp 18 [xv] ibid. pp 13 [xvi] ibid [xvii] ib. pp 13-4 [xviii] Lithopedion from the Case of Dr. William H. H. Parkhurst, 1853. Grace Parkhurst Bernard. Bulletin of the History of Medicine. Vol. 21, 1947. pp 377-8 [xix] Ibid. pp 378 [xx] Ibid pp 380 [xxi] Ibid pp 381 [xxii] Ibid. pp 381-2 [xxiii] Ibid. pp 382 [xxiv] Ibid. [xxv] Ibid. pp 383 [xxvi] Twin Lithopaedons: a rare entity. Mishra J. M., Behera T. K., Panda B. K., Sarangi K. Singapore Medical Journal 2007; 48(9); pp 866 [xxvii] Ibid. [xxviii] Ibid. pp 867 [xxix] Ibid. [xxx] Ibid. [xxxi] Ibid. pp 866-7 [xxxii] Ibid. pp 867

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

November 2013

|

MOST VIEWED POSTS

© James Edward Hughes 2013

RSS Feed

RSS Feed