Merlin. Photo © Save the Manatee Club Merlin. Photo © Save the Manatee Club Having recently become the adoptive parent and “Guardian” of a beautiful Manatee called Merlin, I thought I would write a post about him, and about the Save the Manatee Club, who run the Manatee Adoption Program. Merlin: Merlin, named after the famous Sorcerer, was first identified in 1970, making him at least 41 years old at the time of writing. This is not unusual for a Manatee, as the creatures can live for up to 60 years. He returns each winter to the Blue Spring State Park, near Orange City, Florida, to warm himself in the tepid waters. He is of average size, being about ten feet long (about three meters). Although Merlin is often seen around some of the other Manatees in the Adoption Program, such as Deep Dent, Lucille and Troy, he does like to spend time on his own, and is known to be a little shy around people. He often turns up later than the other Manatees, earning him the nickname “Tail-End Charlie” from one of the Rangers. Like other Manatees, Merlin has received some horrific injuries from boats which navigate through their habitat. Merlin has received extensive damage to his back and tail as a result of various collisions throughout the years. He is, however, a survivor, and can still be found playing and snoozing in the Florida waters. Save the Manatee Club: The Save the Manatee Club was set up in 1981 by singer/songwriter, Jimmy Buffett, and former U.S. Senator Bob Graham, when he was governor of Florida. It is a not-for-profit organisation which seeks to “protect endangered manatees and their aquatic habitat for future generations” through various programs and interventions, ultimately resulting in the “delisting” of the manatee as an endangered species. The difficulties that the Manatee populations face are manifold: loss of habitat, watercraft collisions, pollution, litter, flood control structures, and general harassment from the public and unscrupulous tour agencies. The Save the Manatee Club website states that “since record-keeping began in 1974, more than 41% of manatee deaths where cause of death was identified were human-related – and almost 34% were due to watercraft collisions (the largest known cause of manatee deaths)”. The work of the Save the Manatee Club is focused in the four areas: public awareness and education; sponsoring research, rescue and rehabilitation efforts; advocating strong protections measures; taking legal action where appropriate. They also assist other areas with manatee populations, such as the wider Caribbean, South America and West Africa. Another part of the great work of this organisation is the Adopt-A-Manatee program, where members of the public and organisations can choose a specific manatee to adopt. There are five levels of adoption – Associate, Friend, Sponsor, Guardian and Steward – each with its own sponsorship cost. Lists of adoptable manatees can be seen here. Further information about what you can do to help these beautiful creatures can be found at the Save the Manatee Club website: www.savethemanatee.org. You can also look through its annual report and 2011 highlights.

0 Comments

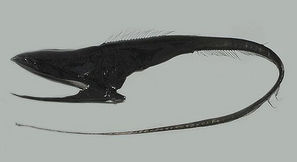

The Gulper Eel The Gulper Eel

The latest subject in the Ocean Wildlife series is the Gulper Eel. This has to be one of the strangest looking creatures in the sea, and given what we have seen already on the site, that is saying something!

The Gulper Eel, other wise known as the Pelican Eel or the Umbrella Mouthed Gulper, has the scientific name Eurypharynx pelecanoides, and is in the order of Saccopharyngiformes. Though they are not true eels, nor are they of the order of true eels, they look vaguely similar: just with an extremely big mouth! They are normally black or dark green in colour, and they live in the extreme depths of the oceans, between 500m and 7500m down, which is why so little is known about it. Deep down in the depths of the ocean, food is scarce, so most of the animals down there have evolved some highly specialised feeding mechanisms. The Gulper eel has adapted in two specific ways. The first is its giant mouth. The head of the Gulper Eel is about a quarter of its total length, which is normally between one and two meters. The jaws are hinged, so that the Gulper can ingest food bigger than its own body. It also uses its mouth like a trawler, increasing its chances of catching smaller, quicker food. The stomach of the Gulper Eel can also distend in order for it to eat and digest large meals. As the jaws of the Gulper Eel are so big, vast amounts of water are ingested. Their method of dealing with this is to use the gill slits to slowly expel the excess water. The second evolutionary modification of the Gulper Eel is its tail, which is very long and thin, and some of the ones found in fishing nets were discovered with knots in the tails. While the long tail is primarily used for movement, there has been a more interesting discovery: the tip of the tail has a developed a photophore, an organ which produces light by a process called bioluminescence. The light produced is usually pink in colour, but the Gulper Eel can produce red flashes. As most of its prey is small and fast, it is thought that the bioluminescence is used as a lure, getting inquisitive victims close enough for the Gulper to snatch. It usually feeds on cephalopods (squid), crustaceans and small invertebrates. As the Gulper Eel has very small teeth, it is unlikely that it regularly feasts on larger animals, though it probably does so if it is forced to. The known predators of the Gulper Eel are Lancet Fish, though other deep sea predators are thought to prey on it. There are other interesting features that are worthy of note. Like all Saccopharyngiforms, the Gulper Eel lacks some of the bones present in other inhabitants of the oceans: these include the lack of a symplectic bone, and the bones of the ribs and the opercle. Also, they have no scales, pelvic fins, or swim bladder, and only very tiny pectoral fins. The lateral line, a sense organ used to detect vibrations in the water, projects from the body, instead of being concealed in a grove in the body. Most intriguingly, it has very small eyes, which is unusual in deep sea animals. It is possible that the Gulper’s eyes are used to detect the presence of light, rather than detailed images. We do not know very much about the reproduction cycle of the Gulper Eel. What is known is that the male Gulper Eel undergoes changes in the maturation process which result in an enlargement of the olfactory organs, and the degeneration of the teeth and jaws, while the female of the species does not. It is likely that the enlarged olfactory organs are used to detect pheromones from the females. Some researchers are of the opinion that the Eels die soon after copulating. Please do have a look at the video below which has footage of the Gulper Eel, starting at 0:37.  Leafy Sea Dragon Leafy Sea Dragon I have not posted anything in the Ocean Wildlife section for a while, so I decided to correct this by telling you all about a very strange sea creature: The Leafy Sea Dragon. The Leafy Sea Dragon, native to the Southern and Western coasts of Australia, gets its name from the leaf-like protrusions which cover its body. These protrusions enable the Leafy Sea Dragon to camouflage itself as a piece of floating seaweed. It has two translucent sets of fins, a pectoral fin on the ridge of its neck, which it uses to steer itself through the water, and a dorsal fin towards the tail, which it uses for propulsion. Its nose and general upper body shape is reminiscent of the sea-horse, to which it is related. Unlike the sea-horse, however, the Leafy Sea Dragon is unable to move its tail, and cannot hang on to seafloor foliage during rough weather. The Leafy Sea Dragon is part of the Syngnathidae family, along with seahorses, pipefish, and the weedy sea dragons. The family name is derived from Greek: syn meaning fused or together and gnathus meaning jaws. The fused jaw is a feature found in the whole family. Another trait of this particular family is that the males of the species carry and incubate the fertilised eggs. Unlike male seahorses, who store the eggs in a specialised ventral pouch, the male Leafy Sea Dragon stores the eggs on a brood patch which supplies them with oxygen. They are placed on to the male's body via a tube extending from the female’s body, which deposits the eggs on the underside of the male's tail. While the female can deposit up to 250 bright pink eggs on for incubation on the male’s body, only about 5% of those will reach maturity, which is about 2 years. The Leafy Sea Dragon is slightly bigger than most seahorses, averaging about 8 to 10 inches (20 to 24cm) long, but can reach up to 18 inches. At the head end of its weird and fabulous body is a pipe-like snout, with which it catches its prey. This snout is also a common feature of the Syngnathidae family. Sea dragons feed mainly on larval fish, amphipods, and small shrimp-like crustaceans called mysids, otherwise known as "sea lice". Most of its prey lives on the red algae which makes its home in the shade of the kelp forests which is one of the main habitats of the Leafy Sea Dragon. Leafy Sea Dragons are also found by rocks, jetties, and raised sand dunes in water no more than 50m (164 feet) deep. Most of the dangers faced by the Leafy Sea Dragon are man-made. The main danger is that of a change in the conditions of its natural habitat. As the Leafy Sea Dragons live in relatively shallow waters, the effects of man’s lifestyle are all to easily felt. Sewage outlets can poison both the Leafy Sea Dragon and its food sources. Boating, and the anchoring of boats, can also damage the delicate eco-systems that sustain the creatures, as can dredging, which destroyes the habitat of its prey. Trophy hunting was a major factor in the decline of the species, as the strange appearance of the creature made it valuable for collectors of exotic marine life. The Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 protects the Leafy Sea Dragon from unscrupulous collectors. People attempting to catch them without a permit can face a fine of up to 11,000$, and a custodial sentence of up to 3 months in prison. There are captive breeding programs in existence, but special care is needed to make sure they survive in captivity. One final interesting fact about the Leafy Sea Dragon is that its eyes move independently of each other, enabling it to see in different directions at once. For more information on the Leafy Sea Dragon, please see the video below. More resources can be found in the list below the video. Further Resources:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leafy_sea_dragon http://divegallery.com/Leafy_Sea_Dragon.htm http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/sea-dragon/ http://news.bbc.co.uk/earth/hi/earth_news/newsid_8330000/8330705.stm http://marinebio.org/species.asp?id=31 http://www.uwphotographyguide.com/leafy-sea-dragon http://www.isidore-of-seville.com/seahorse/7.html http://www.buzzle.com/articles/leafy-sea-dragon-facts.html http://australian-animals.net/dragon.htm  Mola Mola by Richard Herrmann Mola Mola by Richard Herrmann Ever wondered what the largest bony fish in the world was called? Well, it's the Ocean Sunfish, otherwise known as the Mola Mola. The word "Mola" comes from Latin and means "millstone" - a reference to the Sunfish's shape. Averaging about 1000kg (2200lb), this fish is no pushover. In fact, it's only real predators are Sea Lions, Killer Whales, Sharks and Humans. Often called the "giant floating head", the Sunfish looks like it lacks a true body. The other distinctive feature of the Mola Mola is its rather odd propulsion method. As it has no real body or tail with which to swim, the Sunfish has evolved larger than average dorsal and anal fins, which it moves from side to side in a "sculling" motion. It is this motion which can be used to distinguish the Mola Mola from a shark, especially as the Mola Mola is often seen swimming very near to the surface. The large size of these two fins can make the Sunfish as tall as it is long. The skin of the Sunfish is filled with parasites. To be rid of these pesky stowaways, it visits cleaner fish such as reef fish, which eat the parasites. It also lies flat on the surface of the ocean, to allow seabirds to feed on the parasites. This sunbathing technique is also thought to be a way of warming the body after the long dives into the deeper, colder waters of the ocean. Finally, the Sunfish has been known to breach the surface of the ocean, splashing back down hard in an attempt to dislodge the parasites. The first video below is from the National Geographic YouTube channel, while the second is of a talk by marine biologist Tierney Thys from the TED (Technology, Education, Design) website: www.ted.com She has also created the definitive Mola site called The Ocean Sunfish. This super site has loads of facts and figures, and also has a place where you can Adopt a Sunfish. Also, there is an extensive list of resources after the second video. © James Edward Hughes 2011 Resources:

http://www.oceansunfish.org/ http://www.oceansunfish.org/Potter%20and%20Howell%202010.pdf http://www.oceansunfish.org/lifehistory.php http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ocean_sunfish http://www.glaucus.org.uk/Sunfish.htm http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/mola/ Ocean Sunfish By Deborah Coldiron http://www.angelfire.com/mo2/animals1/tetra/oceansunfish.html http://science.jrank.org/pages/4835/Ocean-Sunfish.html http://weirdimals.wordpress.com/2010/10/14/ocean-sunfish-2/ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-highlands-islands-11082731 http://animalcrossing.wikia.com/wiki/Ocean_Sunfish http://www.oceansunfish.org/evolution.php http://www.swansea.ac.uk/bs/turtle/reprints/Pope_etal_2010.pdf http://www.microwavetelemetry.com/newsletters/spring_2007Page5.pdf http://www.wisegeek.com/what-is-an-ocean-sunfish.htm http://www.itsnature.org/sea/fish/the-molas/ http://oceanwildthings.com/2010/09/ocean-sunfish-holy-mola/ http://www.seaturtle.org/ghays/reprints/Houghton_JMBA_2006.pdf http://www.physorg.com/news73056143.html http://www.jstor.org/pss/1436634 http://sciencelinks.jp/j-east/article/200618/000020061806A0676759.php http://research.allacademic.com/meta/p_mla_apa_research_citation/1/8/6/8/0/p186805_index.html http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1937.tb00818.x/abstract Nature's Champions: The Biggest, the Fastest, the Best By Alvin Silverstein, Virginia Silverstein, Virginia B. Silverstein http://www.oceansunfish.org/MolageneticsMarBio05.pdf http://www.oceansunfish.org/ParasiteList4.pdf http://www.oceansunfish.org/DewarEtAlJEMBE.pdf http://sabella.mba.ac.uk/2437/01/sims.pdf http://www.swansea.ac.uk/bs/turtle/reprints/Hays_etal_JEMBE_2009.pdf http://www.springerlink.com/content/pw2760r3553l86j7/fulltext.pdf http://www.asknature.org/referenceMaterial/edeb83d6a24b1fe60b9f07d219c41a67 http://eebweb.arizona.edu/COURSES/Ecol183/lectures%20pdf%202005/sunfish.pdf http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2003.00088.x/full http://www.oceansunfish.org/Potter%20and%20Howell%202010.pdf Photography: http://www.earthwindow.com/mola.html http://www.oceanlight.com/html/mola_mola.html Videos: http://wn.com/ocean_sunfish  Beluga by Midnights Garden Beluga by Midnights Garden It is a pleasure for me to write this post, as I consider the Beluga Whale to be one of the most beautiful creatures on earth. Often called White Whales, the Belugas (Beluga meaning "White One" in Russian) are, for me, the closest a living thing can be to an Angel. They are very popular with, and have good relations with, the human race, and have even been known to save human lives on occasion. Its proper name is Delphinapterus leucas, the latter part meaning white, the former meaning "without fins", as the Beluga has no dorsal fin. This makes it easier for the animal to swim under the Arctic ice. The Beluga is about 13 to 20 feet (4 to 6.1m) long, and are smallish in whale standards. They weigh about 3,300 pounds (1500kg), with males being slightly larger than females. This makes them smaller than most whales. Another difference between the Beluga and other whales is the fact that their neck vertebrae are not fused. This allows them far greater mobility in the head and neck, and also more facial expressions. It is this which allows them to have that beautiful smile, for which they are known they are known and loved. The Beluga is also known for the varied sounds it makes, and has been given the name "Sea Canary" as a result. These sounds are so loud that they can even be heard above the surface of the water. They not only use a huge range of clicks, whistles, and clangs, but can also mimic many other sounds. This proliferation of diverse sounds allows for high levels of communication, and indeed the Beluga is a very sociable animal. You can hear some of their squeaks, clicks and calls here on the BBC Website.  Beluga Whale by jspad Beluga Whale by jspad They have a large melon dome on top of their heads, which makes it look as if they have an extremely large brain. This protuberance is malleable, and the Beluga can change the shape of its head by blowing air around its sinuses. It is thought to contain a very fine oil, which is used as a way to focus the sonar waves it produces to sense its surroundings. They usually swim in small groups called pods of between 2 - 25 whales, and will hunt and migrate together. The Arctic and sub-Arctic waters are the natural home of the Beluga, though fossils show that their territory expands and contracts with the extent of the Arctic Pack Ice. Belugas do sometimes migrate south into warmer waters, mainly in the summer months. The Beluga's habitat overlaps with that of its closest living relative, the Narwhal. Being a slow swimmer, about 2 - 6 mph (3 to 9 kph), Beluga are opportunistic feeders. They can reach a speed for about 14mph, but only in short bursts. They feed mainly on cephalopods and crustaceans, but also on worms living on the sea-floor. A typical Beluga dive lasts for a mere 3 - 5 minutes, but they can stay under for up to 20 minutes, and have been know to dive well over 1000 feet (300m) down. The main predators of the Beluga are Polar Bears and Orca. Orca, of course, will hunt them in the open ocean. Polar bears are able, when the Beluga become trapped in the Arctic Ice, to haul them out of the air holes as the Beluga desperately try to breathe.  Beluga Whale by Pocketwiley Beluga Whale by Pocketwiley The Beluga usually reproduces, once every three years, to one live calf at a time. The gestation period is 14 - 15 months. Interestingly, the calf is born a bluey-brown colour, turning grey after about a year, only changing to the more usual white after about 6 years. The baby Beluga is about 4 - 5 feet (1.2 - 1.5 m) long, and weighs about 180lbs (80kgs). For the first 2 years of its life, the baby Beluga relies on its mother for everything, and feeds exclusively on her fatty milk (28% fat). They reach maturity aged about 8 years. Below is a video of the birth of a beluga calf. Notice how it instinctively makes for the surface straight after coming out.  Marine Park, Beluga Whale by Travlinman43 Marine Park, Beluga Whale by Travlinman43 The Beluga has a long history with Humans, being one of the first whale species in captivity. Barnum's Museum in New York City held the first captive viewing of a Beluga in 1861. Since then, it has remained one of the most popular aquatic attractions around the world. The relation between Human and Beluga goes much further than this, however. There have been many reports of the whales' interventions when divers or swimmers get into trouble. One such story was the case of Free Diver Yang Yun, who was saved by a Beluga called Mila at Polar Land in northern China. Yun started to experience excruciating cramps, which left her unable to reach the surface to breathe. As Yun started to choke, Mila sensed her distress, and came to her aid, gripping her leg with her mouth, and gently driving her up to the surface. Yun said: “I began to choke and sank even lower and I thought that was it for me – I was dead. Until I felt this incredible force under me driving me to the surface.” Read the full article here. There's also a Beluga group on Flickr, which you can see here: Delphinapterus leucas (Beluga Whales). I'll leave you with a video of a playful Beluga blowing bubbles and catching them at an aquarium.  Sperm Whale Scientists in Australia have found a link between Sperm Whale poo and the absorption of atmospheric CO2. You may be sitting there thinking "What a load of crap!", but seriously, it's true! The reason is: Iron. Specifically the amount of iron in each Whale-plop. Those same scientists estimate that Southern Ocean Sperm Whales deposit around 50 tonnes of iron each year. You may be asking yourself why this is important? Well, the increased iron stimulates the growth of phytoplankton which, being a plant, absorbs CO2 during the process of photosynthesis. Phytoplankton rely on iron from growth, to the amount of iron available directly relates to the levels in the sea. The estimate is that about 400,000 tonnes of carbon is absorbed each year, which is only half the amount they produce through breathing. Although the amount is very small compaired to the scale of the problem, the global total, including all Sperm Whale populations, could be much higher. Below are a few pictures of Sperm Whales. But not of their poo! © James Edward Hughes 16/06/2010

Manatee Following my previous post about these beautiful creatures, I wanted to post this video I found on YouTube about irresponsible tourism with respect to the American Manatee. I found this video difficult to watch. Not all tour operators are like this, and there are many that provide a great opportunity for people to have unforgettable encounters with these majestic creatures. It's down to us to make sure we book tours and visits with those operators that have a proven track record when it comes to respecting the needs of the Manatee. Again, do check out the Save the Manatee Club website for more infomation.  Sixgill Shark Another video of the rare Sixgill shark, so called because it has... well you get the picture. Featured before on Show Me Something Interesting, the sixgill seems to be one of your favourites, so here is another chance to see it. This time, the video is from the BBC Wildlife team with Kate Humble. The sixgill usually grows to about 15 feet, but the one in this video is about 20 feet long. Watch it go for the tuna bait that was left by the team. Also, check out the dorsal fin: it's smaller and much further back than usual.  The Fangtooth The Fangtooth The Fangtooth gets its name from its, well, fangs. They are, according to Sir David Attenborough, the biggest teeth relative to body size in the ocean. It has special cavities, which extent either side of its brain, to house the teeth when its jaw is shut. Because they are so ugly, they are also know ans Ogrefish. Their real name is Anoplogaster cornuta, and is from the family Anoplogastridae. They have been found as far down as 16,000 feet, which is one of the deepest descents of any ocean creature yet known. It is so resiliant, that scientists have managed to keep specimines alive for months in tanks inspite of the massive difference in pressure from its natural habitat. Do keep an eye out at the begining ofthe video for a quick shot of the Dumbo Octopus.  Underwater Brine Pool Underwater Brine Pool Another interesting clip from David Attenborough's The Blue Planet: here we see an underwater lake with its own shoreline of muscles. How can this be? Well, it's all to do with the composition of the lake. The liquid in the lake is Brine. Brine is a solution of salt in water where the saturation level is much higher than that usually found in the sea. Because the Brine is heavier than the surrounding sea water, it sinks, and forms pools and lakes at the bottom of the ocean. The pool in the video is in the Gulf of Mexico. This pool was formed when, during the middle Jurassic period, a part of the ocean became cut-off from the main body of water. This then evaporated, leaving behind a high concentration of salt. When normal tectonic movements caused the area to flood, a process called salt tectonics occured, which eventuated in salt being released into the ocean water, and forming a heavy liquid layer layer on the ocean floor. The reason for the shoreline of muscles is that Brine often contains high levels of Methane, which the muscles can process into into energy. These muscles are contain bacteria which are known as Chemoautotrophs: organisms which produce energy by Chemosynthesis. Chemosynthesis is a process where carbon, taken usually from Carbon Dioxide or Methane, is converted into organic matter by the oxidation of inorganic compounds, usually Hydrogen Sulphide, but sometimes by Hydrogen gas. It is this process that allows tube worms to extract energy from the Hydrogen Sulphide produced by ocean floor vents. |

MOST VIEWED POSTS

© James Edward Hughes 2013

RSS Feed

RSS Feed